Homesteading: Emu Does a Bad Thing

(Thrice)

The summer is not quite winding down yet, and it already seems too short.

Today, we travel to Williamsburg, Virginia, so that I can speak at the Pastor Boot Camp. I will be glad to be around like-minded people and look forward to speaking, but gosh-darn - I love being on this farm, on the land, with the animals and puttering about fixing my cars and equipment.

About five years ago, while shopping at Walmart - yes, occasionally we do shop at Walmart, I own that- they had some Chinese-American hybrid chestnut trees marked down as the growing season was coming to an end.

I think they were either fifty or seventy-five percent off, because we bought quite a few of them.

Well, this year, with all the rain, they decided to produce a lot of chestnuts!

Here they are - beautiful trees - still young but established along the edge of one of the horse pastures.

The “Redwoods of the East"

At one time, the American Chestnut was the predominant tree along the eastern coast and mountains of the USA. These tall, stately trees were large in circumference. They are the trees that built all the beautiful colonial and pre-Civil War houses, like Monticello, that have stood the test of time. In large part due to the superior qualities of chestnut lumber.

Then, in 1904, at the Bronx Zoo in New York City, the chestnut trees began sickening. A blight, most likely imported on trees from Japan or China, had declared itself. By the 1930s, the fungus had spread rapidly throughout the natural range of the tree in the Appalachian Mountains and eastern U.S. forests. By 1940, the blight had killed an estimated 3–4 billion trees, reducing the American chestnut from a dominant canopy species to a stump-sprouting shrub.

The American chestnut trees and forests were wiped out. Gone. As forests do, other trees became dominant - but none so stately as the American Chestnut.

Since then, Chinese chestnut trees, which are resistant to the blight, have been imported en masse. The American Chestnut Society has been hybridizing trees to produce a (mostly) American chestnut tree resistant to blight by crossing to the Chinese Chestnut, and they have had success in creating such a tree. But repopulating the forests seems near next to impossible.

Of note, the American Chestnut is a huge tree that towers 100 feet or more above the ground, whereas the Chinese chestnut tops out at about 40-60 feet. The forests in the United States must have been magnificent, with these large trees providing endless shade (and food for native humans, deer, elk, and other animals). The undergrowth, as we know it in the east, must have been so different, with the dominant prey species being elk as well as deer, who would graze under these large trees. Such trees and animals reduce the undergrowth, so walking in the relatively open forest floor with a huge shaded canopy above, must have been a vastly different experience from walking in the eastern deciduous forests of today. Eastern elk, native to these lands, ranged through these forests, roaming freely. Unfortunately, this subspecies was hunted to extinction by the late 1800s (the last known Eastern elk was shot in Pennsylvania in 1877).

There is a movement to bring elk back to Virginia. But of course, don’t laugh (I did), when Jill heard about the program, she thought elk might be a good idea for the farm. No, we are not getting any elk. Or any other exotics - unless they somehow sneak past the gate when I am not around… Well, except the Emu. And who know what else in the future.

Back to the American chestnut, it was one of the most valuable timber trees in the East before the blight. It was prized because the wood was strong, light, straight-grained, easy to split, and naturally rot-resistant (similar in durability to modern pressure-treated lumber).

The American chestnut was called “the perfect tree” because it provided durable, rot-resistant lumber for construction and furniture, tannins for industry, and nut harvests for people and wildlife. Its loss in the early 20th century was not just ecological but also a profound economic blow to rural communities.

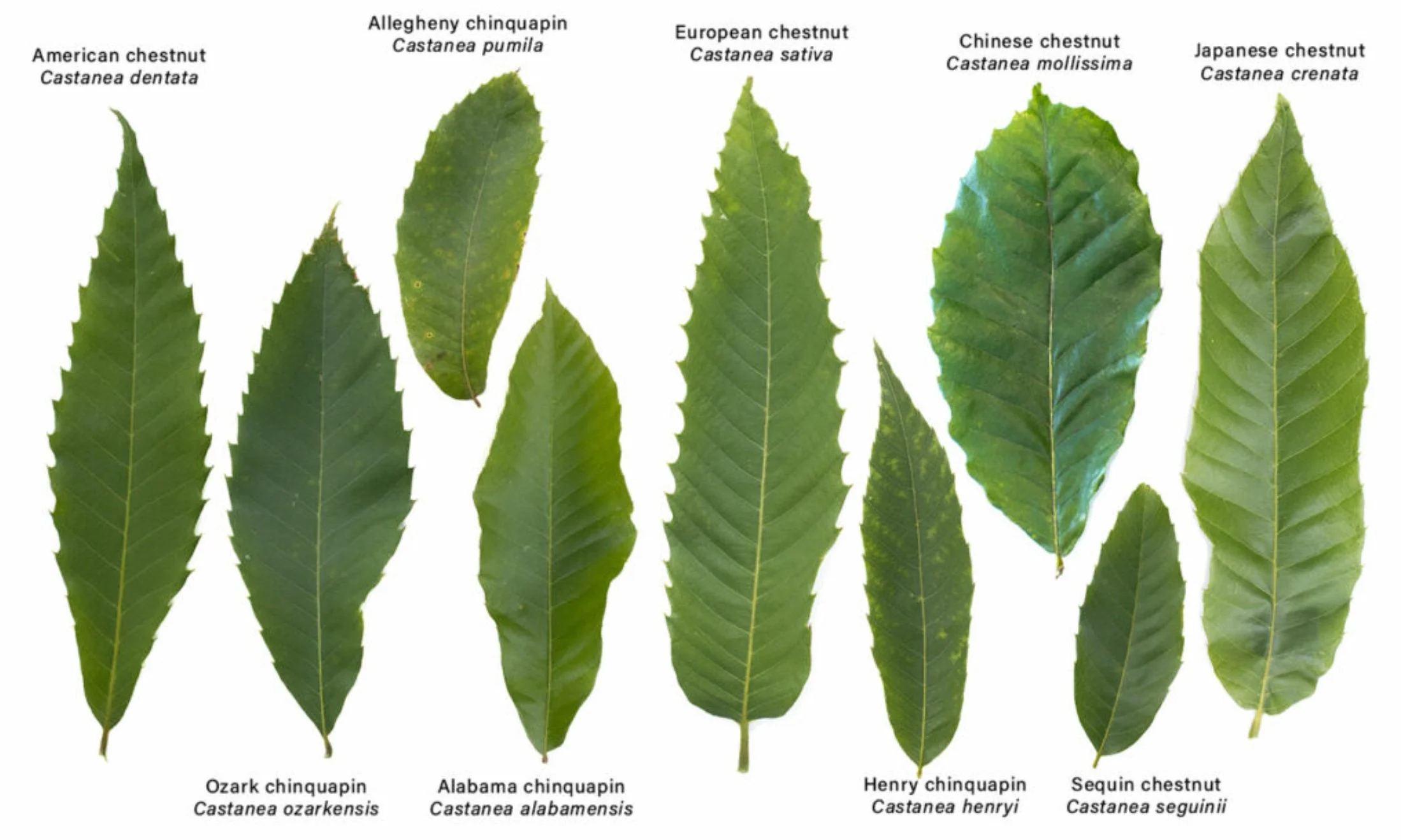

For those interested, below is a chart comparing the leaves of the various chestnuts, followed by a chart comparing the nuts (the American nut is considered sweeter, but the Chinese has a larger nut, which is easier to harvest).

To me, it appears that our trees are a hybrid, although our leaves look more Chinese than American. We have a goal this year to purchase from the American Chestnut Foundation -American Chestnut trees. We will use these as plantings in our small forest and around our pasture lands.

In any case, I am looking forward to harvesting our hybrid chestnuts in the next couple of months! It will be a first for us.

Foraging for nuts in the forest will soon commence!

On our “enforced” walk-about today (more about that later), Jill noted that the pecan or maybe hickory trees in the forest have dropped some nuts, with the hulls still green. What we saw today were hickory nuts; on the other side of the pasture are some pecan trees. We are looking forward to foraging for both.

Pecans are longer, hickory nuts are more round - both are technically hickory nuts.

Gizmo does a bad thing (thrice).

The fall and winter are when emus breed and lay eggs. So, evidently, at two years old, Gizmo the emu has decided she no longer wants to wait around for a mate to show up at her door. So she has decided to take matters into her own hands, and decided that it is time to find a mate. Henceforth, she has determined to take long walk-abouts off the farm to find a partner.

Two weeks ago, before she could be put to bed for the night - goose and emu sleep in a horse stall- she left and spent the night off the farm, returning the next morning. After spending an hour at twilight looking for her, we spent a sleepless night worrying.

Not cool.

Unfortunately, last week, she also did another walk-about - going up around, over hill and dale. I was alerted by a neighbor, and I walked her back to the edge of the forest, where Jill took over on her stallion Jade and herded her back to the farm through the forest path. As Gizmo is frightened of forests, it was good to have the power and speed of a horse. Although truth be told, once Jade showed up on the scene, Gizmo walked out in front - with Jade following close behind.

Today, we received a call from another neighbor saying Gizmo was about a half mile away.

Well, we armed ourselves with our trusty manure folks (soft-tongued rakes) and hopped in the trusty Kubota RTV - which doubles as a Peacock roosting device, when not in use by humans….

Off we went. We found Gizmo, which another neighbor had locked up in an empty pasture. With careful emu herding and many trials, tribulations, ruffled feathers, and short breakaways, we ambled back to the farm.

Gizmo has now been locked up in a pasture, with Gonzo (the goose) for company.

So, it goes. Gizmo will no longer have free range of the farm.

In the meantime, the Peacock named Prince Caspian (or Pied - as I like to call him) found other roosting places.

Vegetables

The vegetable gardens are doing well, given that it is August. We are heading into the hot and dry season around here, so watering almost daily becomes essential. This summer, we have had an abundance of produce to eat - cucumbers, squash, tomatoes, carrots, basil, peppers, blue and black berries, peaches, and more!

Jill has been processing tomatoes, basil, and peppers as well as fruit regularly, and our freezer is filling up. She also made pickled onions - the recipe follows at the end of this Substack (paid subscription only), for those of you who wish to try something different. British pickled onions are truly a treat, sweet, a little spicy, and crunchy.

What the garden looks like this week:

A note about freezers: Home Depot sells a wonderful frost-free upright freezer. The chest freezers that are cheap, are just that. They are almost all manual defrost, which is just another chore to take care of every year. To defrost yearly also requires removing all the frozen goods out of the freezer first. The upright version is brilliant, as it truly is frost-free.

Fall is coming.

Soon, we will begin preparing some of the beds for planting the fall crops.

This will include carrots (yes, we still have carrots that we are harvesting in the garden), kale, lettuce, spinach, beets, and cabbage. And soon after that, in the fall, we will plant next year’s garlic.

Coming up fast in the garden are at least twenty pumpkins - some of them are just starting to turn orange. I am not sure what we will be doing with so many pumpkins this fall! Making lots of puree to freeze, I am sure, and maybe inviting a family or two over to pick pumpkins for Halloween.

The Wild birds have been a joy this year.

The goldfinches were enjoying the sunflower heads up until about a week ago, although the sunflowers are pretty much finished now.

The American Goldfinch was historically known as "Audubon's Finch," which is the name I knew it as when I was growing up. At some point, in the mid-century, that name got changed. It always seems a shame to me - Audubon did so much for American ornithology. He deserves to have this bird with the brilliant plumage named after him.

I have hundreds of photos of the beautiful male below. I think I put up a video of him earlier in the month.

It turns out that goldfinches feed their babies on a strictly vegetarian diet and hold off on nesting until early summer. That way, they have plenty of seeds to feed their babies when they hatch out - later in the summer.

This weekend, we had overnight visitors to the farm, and I got the pleasure of spending time with this little tot and her mama (below).

The little girl was entranced by “Aslan,” our concrete lion.

She also really enjoyed the horses, as did her mother.

Next stop - getting ready for the road trip, so signing off for now!

British Pickled Onion Recipe

(Paid Subscribers only)

2 pounds peeled small onions (smaller are preferred) or shallots

2 tablespoons salt

3 +/- cups malt vinegar

2 tablespoons honey

1/2 cup granulated sugar

1 tsp whole or ground coriander seeds

1 tsp mustard seeds

1/2 tsp whole black peppercorns

1 1/2 tsp allspice, ground

2 whole cloves

2 bay leaves

Alternatively, eliminate all of the spices and add about 2 +/- tablespoons of a commercial pickling spice).

Directions:

Peel onions, cut larger onions into bite-sized pieces. When possible, maintain cohesiveness (don’t slice).

Put the onions in a bowl, sprinkle with salt, and gently stir with a large spoon or toss to distribute the salt.

Cover and let them sit for half a day or overnight. Hint: don’t let them sit too long, or the amount of “crunch” will be compromised.

Place the onions into a colander, then rinse under the tap to remove the salt.

Drain thoroughly.

To make the brine: Place the vinegar, sugar, honey and remaining ingredients in a pan, then bring to a boil until the sugar is dissolved.

Pack the onions into sterilized glass jars. This recipe makes 2 quarts, plan accordingly.

Pour the hot brine over the onions, distributing the spices among the jars.

Stick a knife or other long object down into the jars to ensure there are no air bubbles.

Wipe the jar rims down with a clean, damp cloth.

Place the canning lids on the jars and screw down while hot to create a vacuum seal.

Keep the jars at room temp for at least 3-4 weeks before eating, preferably 6-8 weeks for best flavor.

Then move the jars to the fridge, where they will keep will keep for 3+ months.

Notes:

Although this recipe calls for a lot of sugar to be mixed in with the vinegar, the amount of sugar actually consumed is minimal, as one does not drink the vinegar. This recipe is not “shelf-stable” - as it has not been hot water processed.

These have not been hot water bath processed, so are not shelf-stable for long-term storage.